A couple of weeks ago (because I am slow to get round to blogging), that Neville Gwynne person was on the BBC again talking his usual nonsense. In case you've forgotten, he's a retired teacher who wrote a grammar book and occasionally pops up in the media with odd opinions and crazy thoughts (he is a big fan of

Michael Gove, which really tells you all you need to know). I

wrote about Michael Rosen's response to him and his antics back in March.

This time, I wanted to talk about correcting people's grammar, and whether it's a good thing or not.

First, let's clear something up. Rosen says (in the article cited in the previous post I linked to)

In fact, we would neither be able to speak nor understand if we didn't know [grammar].

Gwynne says (in his book, on page 5)

For genuine thinking we need words... If we do not use words rightly, we shall not think rightly.

(Note his use of the hideous adverb 'rightly' because of his obsession with not using adjectives as adverbs!)

These are two very different positions, and I agree wholeheartedly with Rosen and disagree wholeheartedly with Gwynne. Rosen is right because language is, basically, grammar. 'Grammar', when not used in the school sense, is simply the way language works. Without it, you just have a bunch of sounds and maybe not even that. But you cannot go from that to saying that thinking requires words. This is a complex philosophical issue and one that I'm not going to get into here. It is possible that thinking does require language (definitely not just words), and if it does, OK, fine, we need to know grammar (not just words) to think, or at least think clearly and in some sophisticated manner which goes beyond what all animals do. But it is absolute fact that we do not need 'correct' grammar to think, and that is the dangerous message that Gwynne peddles.

I can see his argument, but he's got it wrong. He sees well-argued, cogent writing with correct grammar and poorly-argued, badly-written writing and thinks that one leads to the other. No. The two may well be related, but one is not a cause of the other. I see it myself: the most able students are often those who can also write well. The students less able to put together a clear, logical argument also tend to write less well. But this is far more likely to be due to general ability level, which affects both variables independently.

Furthermore, take this video of Boris Johnson and Russell Brand on Question Time (it's a BBC thing on YouTube so if it disappears, just look for any other footage of these two people):

Russell Brand has a persona, and part of that persona is his dialect, which includes many non-standard forms that Gwynne would consider to be wrong. However, Brand is also intelligent and is often booked for these things because people love to see him in opposition to the posh morons in power. He is highly articulate (he also writes well, and has a

newspaper column). He sometimes says stupid things, but he says them all quite well and certainly makes a good, insightful argument. Boris, on the other hand, is educated, probably got taught all this 'proper grammar' stuff, but can barely string a sentence together. His spoken grammar is not 'correct' because he never utters one single 'grammatically correct' sentence. Ever. (I haven't checked everything he's ever said, but his hit rate is a lot lower than Brand's, for sure. Scripted speeches don't count.)

Gwynne teaches mostly non-native speakers of English, as far as I can tell, via the internet. This is admirable. I should think that his students, many of them in developing countries, will benefit greatly from having a good standard of written and spoken English. It is important to teach the standard, because that is what learners will be expected to learn by those who test them and those who judge them for entry to university courses and employment, and it's what they themselves will expect to learn. Some people can go too far with their linguist-centred descriptivist outlook and claim that it's oppressive to do this, but in fact we are failing language students if we don't teach them the standard. Similarly, when I mark essays, I correct them if they don't use standard English. I do think, though, that students should be taught what people really say and what the acceptable alternatives are, alongside what is 'correct'. Sometimes this is beyond the time constraints of the course or the abilities of the student.

Likewise, children should be taught how to use the standard dialect of their language (in their country, as standard US is different from standard British and so on). This will help them to get on in life. But they should not be told that any other way they speak is wrong: if you are a normally developing human, you speak your own language perfectly. There simply isn't any other way to do it. It's like telling a person they walk wrong. Maybe they walk in a way that displeases some people (dragging their heels, or too slowly) but they still walk perfectly fine.

It might not seem that important, but there are serious consequences of views like Gwynne's. In the recent Trayvon Martin case, Rachel Jeantel's testimony given largely in AAVE (African American Vernacular English)

caused a lot of debate. A common example used in sociolinguistics classes is the Oakland school board case from the 1990s: in a county in California, it was decided that something needed to be done to help the black children, who were systematically performing worse than the white children, even when all else was equal. It was suggested that they might be at a disadvantage because they spoke AAVE at home, which is significantly different from standard English, and needed to be taught how to 'translate' it into standard English. This stirred up an enormous amount of racism and eventually the scheme came to nothing. People would rather black children continue to underperform and start their academic life at a significant disadvantage than risk their own children coming into contact with this dialect in the classroom. But the point is, there is no inherent reason why AAVE is not the standard dialect: it's simply an accident of history. What is now the standard is the variety spoken by the people in charge. A good education should teach children how to use the standard as well as their native dialect, but you can't judge a person's intelligence by the dialect they speak.

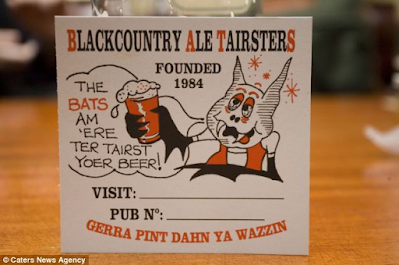

In the UK, there is no equivalent to AAVE. We have Multicultural London English, which is similarly stigmatised, but the two are very different. We do have a lot of regional dialects, though, and these are generally looked down upon and their speakers thought to be stupid, lazy or simply wrong. This means that working-class people, who are more likely to use regional dialect features, have to make a far greater effort than those who grew up with the standard as their native dialect. They may therefore do less well at school, and they may get less good jobs. Given that they are already at a societal disadvantage simply by being working class rather than middle or upper class, this only serves to compound the problem.

Gwynne no doubt considers people who use non-standard forms to be either stupid or lazy (because why else wouldn't they have learnt the correct forms?). Some of them are. But some people who use standard English are also stupid and lazy, and their language doesn't give you an easy way to judge them. Meanwhile, the dialect-users who are intelligent and hard-working are unfairly discriminated against. Young women are routinely judged to be less intelligent, because they tend to use linguistic features that often become mainstream later on. All of this perpetuates an unequal society in which rich white men have greater advantages and poor people, women and ethnic minorities have to work harder to achieve equal or lesser status.