Because I have two long dogs (a greyhound and a galga) I follow long dog content on instagram, and I'm always slightly intrigued by their distinctive dialect. Here's a representative example:

The posts are always written from the dog's perspective, and the dogs have this slightly childish manner of speaking (which is fair enough, they're only young) so they use diminutives like earsies and cutesy words like sheeples in the post above. Their spellings presumably reflect their phonology, so here you can see that this dog has vewy for very, indicating a common variant of the /r/ sound, especially in children. That one isn't necessarily universal, but what is universal to greyhounds is the 'th-stopping' you can see in Dey for They, where 'th' sounds are pronounced as /d/. This dog doesn't have it in all relevant contexts, as elsewhere he says ze for the rather than de or da, which would be more usual. Some of these things are also found in other dog dialects and even beyond, in cat varieties. Others are quite specific to greyhounds.

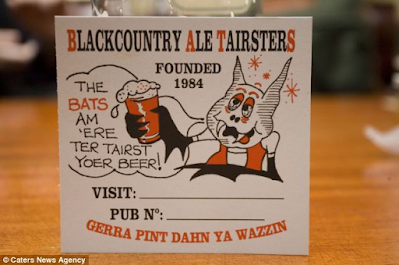

The thing that I spotted the other day was this yam. Yam is well-known as a feature of the Black Country dialect, around Wolverhampton and Dudley, where it's a variation of the verb be. In Standard Englishes you get am just for first person singular (I am). In many varieties you get levelling so that was or were is used for all the forms in the past tense (I were) or even is in present (you is). I think this is a form of levelling too: am is used for other persons than 1st singular, as in the message from the Black Country Ale Tairsters (tasters) below: The BATs am 'ere ter tairst yoer beer!.

Then you get it running together with the pronoun in speech and you've got yam. I did all that from memory (sorry, lots of teaching prep to do this week) so the details might be wrong, but that's about the size of it. But what it isn't, is yam being the pronoun itself. That's what the greyhounds are doing, they're using yam in place of me in standard Englishes, not in conjunction with the verb to be. It's not a one-off from Finn the greyhound either, it's pretty standard Greyhound. So they've innovated or borrowed a new first-person pronoun.