I've held off on blogging about Wordle, because everyone else did it, and because I didn't have anything particular to say. People tend to assume that if you're a linguist, you like word games, but I don't think that's any more true for us than for normal people. Some of us do, others don't. I happen to love crosswords (because there is a quiz or a puzzle element) and dislike Scrabble (because I'm not good at anagrams). I do, as it happens, love Wordle. I love logic puzzles like sudoku, and this is basically just a logic puzzle with an added constraint.

There is, or used to be, a board game called Mastermind which was a pure logic version of Wordle. (If you don't know what Wordle is, by the way, I don't know where you've been. It's what we all spent the early part of 2022 doing.) There, the thing you had to guess was the sequence of coloured pegs. There were only a few colours, and only a sequence of four, so much fewer than the 26 letters and five slots that Wordle involves. And you needed like ten goes to get it, rather than the six that you get with Wordle. The rules were the same: you got told if you'd got one right and in the right place, or right but in the wrong place, or wrong. You weren't told which one, though, which did make it harder in that respect (otherwise it would have been incredibly easy). I loved this game and I'm not sure why I never had my own copy (maybe no one else liked playing it with me, or maybe I never mentioned that I liked it?) but I played it when I was at other people's houses.

So yes, I do love Wordle, because of the logic puzzle aspect. The word part of it does add something interesting for me, though. I like the constraint it puts on the possible answers. It's not the case, as in Mastermind, that every combination is equally possible. Some just aren't, or are much less likely, and that's due to the rules of either languages in general, or English in particular. So an example of a language-in-general thing is that there are going to be some vowels in the word, and some consonants. An example of an English-in-particular thing is that the last letter is probably an 'e' or a consonant, because we don't have so many words that end in 'a', 'i', 'o' or 'u' (though we do have some, so it's not absolutely ruled out). Another English-in-particular thing is that if you know you've got an 'h' in there somewhere, it's possibly the first letter but if it's not, you've likely also got a 't' for 'th' or a 'g' for 'gh' in there. Not always; ahead would have stumped me in that case.

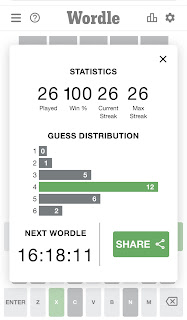

I've been paying attention to how I solve them, and I usually get the answer on the fourth go. I imagine this is true for most people, as we'd expect a 'normal distribution' with very few right on the first or second go (that's a lucky guess) and few taking six (that's some bad luck or a word that has many very similar to it).

I'm not sharing any new insights on how to solve them – I just do the same as you all do and rule out the most common letters first until I can see what it's likely to be. But what interests me is how quickly you get to the point where it can only realistically be one word. This is normally where I am by guess four.

Here are a couple of recent ones, where the answers were epoxy and lowly. Just coincidence that they both end in a 'y', I think. I vary my starting words but always try to include some common letters. Sometimes I just use things I see nearby like the dogs' names. In both these cases, by the time I'd had three guesses I didn't have many right, but I had ruled out nearly all the possibilities, and there was only one possible word that I could think of in each case that could fit what I knew.This is the most satisfying way of playing the game, I think. If you end up with only one letter to get and several possibilities, it becomes chance and annoying, and if you get it right with some lucky guesses you don't feel like you earnt it, whereas this way you feel happy that you worked it out.